Getting Things Done - GTD

Doing Fewer Things: The First Principle of Slow Productivity and Its Connection to GTD

AUTHOR: María Sáez

We live in an era where constant activity has become the visible symbol of productivity. Responding to emails at 11 p.m., being available on multiple communication channels, attending back-to-back meetings, and keeping dozens of projects going simultaneously is perceived as the mark of a committed and productive professional. However, Cal Newport claims (and I quite agree) in his book Slow Productivity: The Lost Art of Accomplishment Without Burnout that this culture of perpetual busyness is precisely what is destroying our ability to produce truly valuable work.

Newport uses the term pseudo-productivity to describe this phenomenon:

The use of visible activity as the main way to approach real productive effort.

In knowledge work, where results are not as tangible as the components that come off an assembly line, we have fallen into the trap of measuring productivity by the volume of activity rather than by the quality and impact of what we produce.

The problem is that this approach is not only unsustainable from the point of view of human well-being, but also fundamentally counterproductive. When we try to keep too many things in the air at once, each new commitment brings with it what Newport calls overhead tax: the administrative cost associated with email exchanges, meetings, calls, and necessary coordination. These small tasks silently consume the time we need for the work that really matters and delays the achievement of goals.

The “Do Fewer Things” Principle, Explained

Newport’s response to this problem is Slow Productivity, a more relaxed alternative that avoids the burdens generated by pseudo-productivity in today’s society. It’s a philosophy for organizing knowledge work in a sustainable and meaningful way, based on three principles:

- Do fewer things

- Work at a natural pace

- Obsess over quality

In this article, we will discuss the first of these principles, do fewer things, which Newport expresses as follows:

Try to reduce your commitments as much as possible to have free time. Take advantage of this lighter load to devote yourself to the small projects that really matter.

The first important clarification is that doing fewer things doesn’t mean achieving less. This is a distinction that many people misunderstand. Newport isn’t advocating mediocrity or reduced ambition. Rather, he’s proposing reducing the number of commitments we actively pursue at the same time. The difference is important.

To put this into practice, Newport suggests implementing a systematic plan to limit significant commitments to three levels:

- Limit your missions. These are the broad outlines that determine where you focus your attention at work. Ideally, you should focus on a single goal, although two or three missions is more realistic and still manageable.

- Limit your projects. In order for missions to progress and be completed, you must initiate projects. Some are launched only once, while others may be recurring.

- Limit your daily goals.

Newport suggests some practical strategies for implementing this system. For example, to limit your daily goals, work on no more than one project per day. This doesn’t mean you only do one thing per day; you’ll still have meetings, emails, and administrative tasks. But it does mean that when it’s time for deep, creative work, you devote yourself entirely to a single project. This calibrated focus produces a much more sustainable and effective work rhythm.

Another key strategy is to make your workload transparent using an “active” and “on hold” system. Imagine you have ten projects on your list. The traditional approach suggests working a little on each one every week, responding to everyone’s requirements, attending everyone’s meetings, and keeping all the balls in the air. The result is that each project progresses slowly, the quality of work on each one is mediocre because you can never give it your full attention, and you live in a constant state of stress trying to remember where you left off with each one.

The “doing fewer things” approach suggests something different. You select two or three projects as “active” and devote your best energy to them. The other seven remain on a waiting list, acknowledged and captured, but not active. When you complete one of the active projects, you pull the next one from the waiting list. The surprising result is that you end up completing more projects in less time, the quality of each is significantly higher, and your stress level decreases dramatically.

Why does this work? Because of the overhead tax we mentioned earlier. Every active project requires not only direct work time, but also time for coordination, context switching, and mental maintenance. When you work on fewer things concurrently, more of your day can be devoted to actually completing these commitments, which means you complete them faster. Plus, the quality is higher because you can give them your undivided attention. The result is that you produce really good work at a much faster pace, making your day less overwhelming and more satisfying and meaningful.

The practical suggestions Carl Newport offers in his book are varied and may or may not be appropriate, depending on the context in which they are applied and the existing corporate culture. I recommend reading the book if you want to explore them in greater depth.

Where Slow Productivity and GTD meet

This is where the conversation becomes particularly interesting for those of us who practice Getting Things Done. At first glance, it might seem that Newport and David Allen’s ideas are in tension, but a deeper look reveals that they are deeply complementary.

David Allen built GTD on a fundamental premise: your mind is for having ideas, not for keeping them. “Open loops” (commitments, ideas, and concerns that you keep in your head) constantly consume cognitive resources, even when you aren’t consciously thinking about them. This diffuse mental load creates stress and reduces your attention span. The solution is to capture everything in a trusted external system, process it regularly, and maintain clear lists of what needs to be done.

This complete capture and mental clarity are precisely the conditions necessary for deep, concentrated work to be possible. As Newport points out in his book Deep Work, trying to do cognitively demanding work while your mind is preoccupied with uncaptured commitments is like trying to run a marathon with a backpack full of rocks. GTD removes those rocks. It provides the peace of mind that allows for the deep concentration that Newport values.

In addition, GTD’s Focus Horizons system provides exactly the framework needed to decide which projects really matter. Once you have clarified your purpose, vision, goals, and areas of responsibility, you have clear criteria for evaluating whether a new project deserves your attention or should be declined or postponed. This is the kind of strategic clarity that makes it possible to say “no” with confidence, something Newport recognizes as essential for limiting daily missions, projects, and tasks.

The Weekly Review, that sacred GTD ritual, becomes the perfect time to apply the principle of “doing fewer things.” It’s not just a time to review lists and make sure everything is up to date; it’s an opportunity to take a step back and ask yourself, “Of all these projects on my list, which ones should really be active this week? Which ones can I genuinely put on hold?”

Both systems also share a fundamental rejection of reactive improvisation. Allen insists that you cannot work effectively “from your inbox,” responding to whatever is loudest or most recent. Newport makes the same argument from a different angle: the culture of always being available and always responding is exactly what destroys real productivity. Both advocate for deliberate and thoughtful systems rather than reactive and chaotic ways of working.

Creative tensions: What Slow Productivity adds to GTD

However, it would be dishonest to suggest that there’s no tension between the two philosophies. Newport has been critical of GTD in the past, and while his criticisms sometimes misinterpret the method, they point to legitimate areas where Slow Productivity can complement and strengthen GTD practice.

Newport’s central criticism is that GTD, as many practice it, can become a system for efficiently managing chaos rather than reducing chaos itself. It’s very effective at organizing shallow work (tasks that are not very cognitively demanding), but it doesn’t offer much guidance on how to protect time for deep work that requires sustained concentration and produces truly valuable results.

There’s some truth to this. GTD is content-neutral. It helps you manage whatever you’ve agreed to do, but it doesn’t tell you what you should agree to do in the first place. You can have a perfect GTD implementation and still be working on too many things at once—you’re just managing them in a more organized way. Your lists are impeccable, your system works perfectly, but you’re still stressed and your most important work is progressing slowly because it’s fragmented among dozens of other responsibilities.

This is where Slow Productivity adds a crucial layer of philosophy on top of the infrastructure that GTD provides. Newport invites us to be more aggressive in limiting what we allow into our system in the first place, and more thoughtful about how many projects we keep active simultaneously.

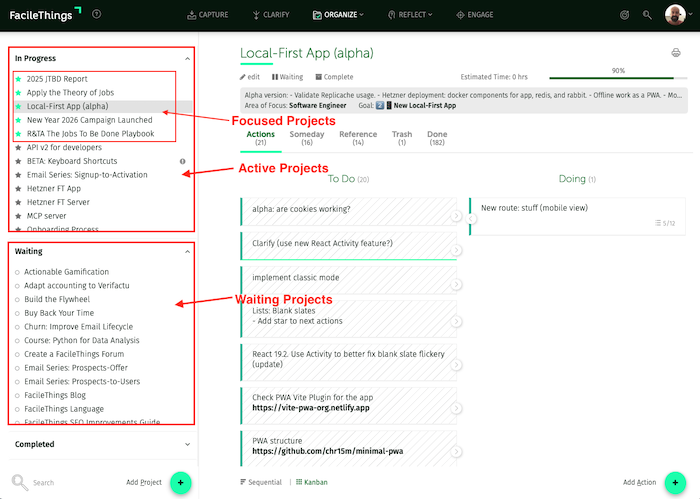

The concept of active projects versus on hold projects is not native to GTD as Allen describes it in his books (although FacileThings implements this possibility). In standard GTD, you have a list of projects, and you are supposed to be making progress on all of them. The only real distinction is between active projects and “someday/maybe” items. But this creates a problematic gray area: everything on your active project list feels like something you should be working on right now, creating constant pressure.

Newport’s proposal to explicitly divide your active projects into “working on this now” and “I’ll do this soon but not now” adds valuable clarity. It’s not “someday/maybe,” it’s real commitments. But you openly acknowledge that you can’t work on all of them simultaneously, so some must wait their turn.

GTD also encourages you to question what your real commitments are through levels of perspective, but this requires a level of reflection that not everyone is willing to do. Slow Productivity places greater emphasis on actively questioning your commitments. If the central clarifying question in GTD is “What’s the next thing to do?”, Slow Productivity adds a preceding question: “Should I be doing this?” It’s not enough to ask how to do something efficiently; we need to regularly ask whether it should be on our to-do list.

Newport also emphasizes prioritizing depth over breadth. It’s better to do three projects exceptionally well than to do ten projects mediocrely. In a culture that values being busy, this takes courage. It means potentially disappointing some people in the short term by declining opportunities or postponing requests. But the long-term result is higher-quality work that builds a stronger reputation and, paradoxically, creates more valuable opportunities in the future.

Conclusion: Methodology plus complementary philosophy

Ultimately, GTD and Slow Productivity aren’t in conflict; they’re two complementary lenses for approaching the challenge of modern knowledge work. GTD provides the infrastructure: the habits, systems, and tools for capturing, clarifying, organizing, and reviewing everything that might require your attention. It’s the operating system that prevents things from falling through the cracks and provides the mental clarity necessary for any effective work.

Slow Productivity provides the guiding philosophy: the values and criteria for deciding what deserves to go into that well-organized system and what deserves your limited attention. It’s the wisdom of how to use that operating system in a way that produces not just efficiency, but truly valuable work and a sustainable professional life.

David Allen taught us that you cannot manage time, you can only manage your actions. Cal Newport adds that not all possible actions deserve to be managed, and that fewer actions managed exceptionally well outperform many actions managed adequately.

Together, these two approaches create something more powerful than either of them alone: a system that allows you to handle the real complexities of modern life without sacrificing your ability to do deep, meaningful work. It’s a system that is both comprehensive and sustainable, both organized and human.

The choice is not between GTD and Slow Productivity, but rather to integrate both of them. Use the clarity and confidence that GTD provides as the foundation to build a slower, more deliberate, and deeper work practice. The result will be less stress, better work, and, paradoxically, even more remarkable achievements.

- o – O – o -

Appendix: Slow Productivity with FacileThings

So how can you integrate these ideas into your GTD practice? Here are some specific suggestions for FacileThings users who want to adopt the principle of “doing fewer things” without abandoning the solid infrastructure that GTD provides.

Start by adapting your Weekly Review. In addition to the usual activities of reviewing your lists, processing your inbox, and ensuring that all your projects have defined next actions, add a new step: decide how many projects will be “active” next week.

Try to dedicate entire weeks to specific projects whenever possible, rather than trying to move forward on all of your projects every week. This doesn’t mean that the others disappear from your system; they remain captured and tracked. But you make a conscious distinction between the projects you will actively work on and those that are waiting their turn. FacileThings allows you to do this because it distinguishes between “in progress” and “waiting” projects.

Another approach is to embrace the one deep project per day rule. Each morning or the night before, identify your deep work project for that day. This is the project that will receive your best cognitive energy in a protected block of time. Schedule this block in your calendar as a non-negotiable appointment with yourself. During this time, you work only on that project, no email, no Slack, no interruptions. The rest of the day can include meetings, administrative tasks, and handling the urgent, but your most important work receives protected attention.

You can mark this project with the star flag, designed to indicate which project you want to focus on. Projects with this flag (and their actions) will always appear at the top of the lists so you can focus on them. During your daily planning, prioritize the next actions for these active projects. The other projects still have next actions defined, but you understand that this week your focus is elsewhere.

Learn to say “not yet” instead of just “yes” or “no.” When someone proposes a new project or asks you to participate in something, and you determine that it’s worth doing but your current workload is already maxed out, you can say, “I’d love to work on this, but I’m currently committed until [date]. Can we revisit this in [next month]?“ Be honest about your actual capacity. Add the catch-up to the ”Someday/Maybe" list with the review date, and review and activate it in the corresponding Weekly Review.

Start measuring your overhead tax. If you find that you have too many meetings about multiple different projects, too many email threads that require follow-up, or that you are constantly switching contexts between unrelated project tasks, these are clear signs of overload. It’s not a sign that you need better organization; it’s a sign that you need fewer active projects at the same time.

This approach will allow you to experience less cognitive stress, because your attention isn’t constantly fragmented between dozens of commitments. The quality of your work should improve, because you can now give real focus to what matters. And, although it may seem counterintuitive, you’ll complete more projects overall, because active projects move forward much faster without the overhead of maintaining everything else simultaneously.

3 comments

You write

In knowledge work, where results are not as tangible as the components that come off an assembly line, we have fallen into the trap of measuring productivity by the volume of activity rather than by the quality and impact of what we produce.

Every organisation that i worked for from 1972 to 2020 measured my work by quality and impact

As those organisations reduced headcount i had to work on multiple activities each day making measurable progress in each

GTD was invaluable in knowing my next action

You write

In knowledge work, where results are not as tangible as the components that come off an assembly line, we have fallen into the trap of measuring productivity by the volume of activity rather than by the quality and impact of what we produce.

Every organisation that i worked for from 1972 to 2020 measured my work by quality and impact

As those organisations reduced headcount i had to work on multiple activities each day making measurable progress in each

GTD was invaluable in knowing my next action

Hi again, Gary.

There’s an objective reason why knowledge work isn’t just more difficult to measure than earlier Fordist models, but often nearly impossible to measure at all: knowledge work is oriented toward modifying the very criteria of production. As a result, it cannot be measured in advance, nor fully while it is unfolding, since it changes the landscape as it proceeds. That said, there are different scales of knowledge work, and in some cases content creation or software development can be tied to achievement trajectories that companies already track.

You’re fortunate to have spent so many years working in companies where knowledge work is acknowledged and understood. This is becoming more common, but it is still far from universal.

We’re glad that GTD helped you in that process.

Hi again, Gary.

There’s an objective reason why knowledge work isn’t just more difficult to measure than earlier Fordist models, but often nearly impossible to measure at all: knowledge work is oriented toward modifying the very criteria of production. As a result, it cannot be measured in advance, nor fully while it is unfolding, since it changes the landscape as it proceeds. That said, there are different scales of knowledge work, and in some cases content creation or software development can be tied to achievement trajectories that companies already track.

You’re fortunate to have spent so many years working in companies where knowledge work is acknowledged and understood. This is becoming more common, but it is still far from universal.

We’re glad that GTD helped you in that process.

Thanks again Maria for your comments. However, I would say that some of those companies measured difficult knowledge work by using Fordist methods. For example, universities measured academic knowledge work by counting number of prestigious journal publications.

I realise that my post last para didnt say what I wanted, because I was rushing to post it in between meetings.

What I meant to write was: Before GTD, namely, 1972-2002, I worked on multiple activities each day, making measurable progress in each by simply using a daily journal/dairy to track where I was up to by project. After GTD, 2003 onwards, I switched to focusing on next actions. For reasons that are unclear to me now, I was only aware of the Getting things Done book by David Allen not this other two (Making it all work; Ready for anything). I was still using the DOS-based Lotus Agenda and created my own GTD template, which no current app matches for functionality, because it would parse the inbox item for me. It was then I discovered that Context needed to be broken into separate components (Location, Person, Occasion, Tool, Resource or Material, Weather).

Thanks again Maria for your comments. However, I would say that some of those companies measured difficult knowledge work by using Fordist methods. For example, universities measured academic knowledge work by counting number of prestigious journal publications.

I realise that my post last para didnt say what I wanted, because I was rushing to post it in between meetings.

What I meant to write was: Before GTD, namely, 1972-2002, I worked on multiple activities each day, making measurable progress in each by simply using a daily journal/dairy to track where I was up to by project. After GTD, 2003 onwards, I switched to focusing on next actions. For reasons that are unclear to me now, I was only aware of the Getting things Done book by David Allen not this other two (Making it all work; Ready for anything). I was still using the DOS-based Lotus Agenda and created my own GTD template, which no current app matches for functionality, because it would parse the inbox item for me. It was then I discovered that Context needed to be broken into separate components (Location, Person, Occasion, Tool, Resource or Material, Weather).